Site Condition Analysis

Consider the existing conditions of a site when choosing plants and locating amenities. Use your observations to create a well-informed design and plant pallet.Sun and Shade

Take time to evaluate the sunny and shady places throughout the day. Determine if the conditions change significantly throughout the day or year. Evaluate if there could be significant changes occurring in the near future, such as construction or demolition of buildings, or tree removal.- Deep shade — the highest shade is behind and alongside buildings. It has very distinct lines, and changes seasonally with the sun’s angle. The north side of a building might have spots that are cold and dark in June, but hot and sunny by July.

- Overlapping shade might occur from multiple building heights, or buildings and trees, or buildings and vehicles.

- Spontaneous shade develops if cars, trucks, or dumpsters are regularly parked nearby during the day. This can create deep shade pockets even on the sunniest sites and you might need to determine if this is a temporary (and for how long?) or permanent condition.

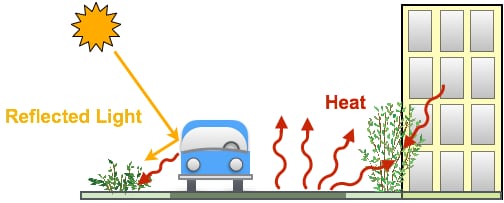

- Light from reflected surfaces like windows and metal from cars, building materials, and signs can burn plants.

- Shade increases the growth of moss and algae on surfaces. Although this can create a pleasant visual effect in some places, it could also be an unwelcome slippery nuisance on walking surfaces.

Suggestions

- For areas with interchangeable shade through the season, choose plants that tolerate a wide variety of sun/shade variance.

- Block reflections with hardy plants or built elements.

- Choose surfaces that provide good traction when wet or are easy to clean off moss and algae.

Heat

Consider sources of heat that might be present on or surrounding the site.- Heat island effect: Cities get hotter and stay hotter for longer, creating a different climate from the surrounding towns and countryside.

- Impervious surfaces absorb heat and radiate it for long periods. This can create a microclimate for certain plant species that are not zone hardy, but it usually does more harm than good by creating high heat and causing soils to dry out fast.

Suggestions

- Choose plants that prefer hot, dry conditions.

- Add trees and shrubs for increased shade and cooling through transpiration.

- Cover the ground with vegetative groundcovers which can help keep soil cooler.

- Create cooler micro-climates by selecting taller plants to provide additional protection for smaller, more sensitive plants.

Stormwater Management

Check the site for ways water enters, moves through, or stays on the site. Start the water management plan as near to the water’s entry point as is feasible and work your way downhill.- Impervious surfaces result from people walking over, standing, parking, storing construction materials, and driving heavy equipment over areas.

- Impervious surfaces cause increased flow and velocity of runoff.

- Lawns and compacted soils don’t allow good water infiltration. Areas might become inundated with water and not be able to drain quickly.

- Evaluate if there are interchangeable periods of extreme inundation and extreme drought.

- Pesticide, herbicide, fertilizer, sediment, petroleum runoff is increased.

- Evaluate if there could be significant changes occurring in the near future, such as construction or demolition of buildings, parking lot expansion, or tree removal. Any of of these changes located uphill of your site, including compaction of soil from large equipment, can impact the amount, direction, and velocity of stormwater flow.

Suggestions

- Increase plant material as an alternative to pavement, lawn, and mulch to help slow water running through the site.

- Design with deep rooted plants to increase water infiltration and decrease erosion.

- Slow water down with berms and stone placement, or spread water out over a flat vegetated space.

- If space allows, create raingardens to catch the first flush of stormwater runoff and keep pollutants on site for filtering.

- Add cisterns above or below ground to collect rainwater. Cisterns come in a range of sizes and shapes that could fit small spaces including narrow, wall mounted models and those that fit under porches or decks.

Soil

Although soil can be challenging on any site, urban sites often present some unexpected challenges. Urban soils generally have experienced significant disturbances, only some which are visible.

- Compaction

- Topsoil could be stripped from the site by construction or erosion.

- Soils might be contaminated from industrial particles, leaking, or dumping.

- Urban rubble might be on or below the surface, or completely different soil characteristics exist from one spot to another — surprise!

- Road debris and trash can be thrown or blown onto the site.

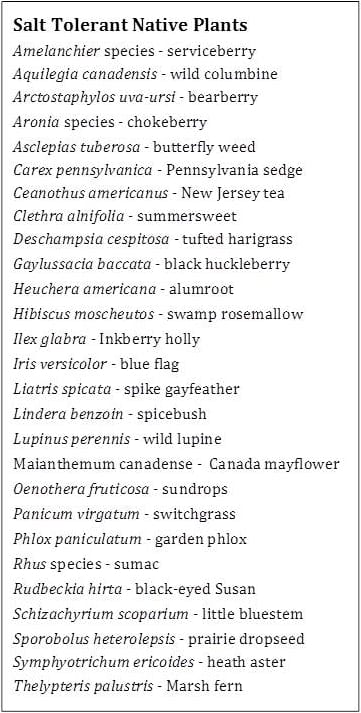

- Salt and pollutants from road and sidewalk runoff might become concentrated in small areas.

- Soil pH can be affected by a wide variety of elements: over-fertilizing can acidify, city water can alkalize.

Suggestions

- Soil testing gives you a good place to start understanding your soil.

- Designing with deep rooted plants improves soil texture, aeration, and texture while also preventing erosion.

- Choose trees and shrubs that tolerate compaction. Many native plants that grow in wetlands tolerate compacted soils because they perform well in low oxygen conditions.

- Cover the soil with plants and mulches to keep contaminated soils covered and prevent dust and splash-back of contaminants onto plants and other surfaces.

- Leaf mulch is a great choice of mulch to reduce watering and insulate plant roots. It holds the most water of any mulch available (up to twice as much as peat moss, depending on leaf variety) and it’s often generated on site for free.

- Specify trash removal as part of the maintenance plan.

- In spring, provide a flush of water to soils that accumulate de-icing salts.

- Extremes of soil acidity or alkalinity can be adjusted with the addition of organic matter, lime, or acid-forming compounds.

Air Movement

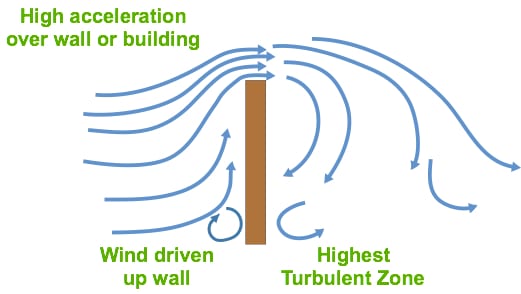

Evaluate for conditions that increase velocity and direction of air on or near the site. Although mild winds of 5 mph can help strengthen plants, strong and turbulent winds can cause added plant stress and injury.- Wind tunnels can develop between buildings and objects such as trailers and large dumpsters, producing colder air that rapidly dries out soil.

- Solid fences create pockets of turbulent air on the leeward side of the fence.

- Wind dries soils out quickly.

- Wind increases plant transpiration, requiring the plant to use more water.

- High wind can shred plant leaves and sand particles can sandblast the entire plant.

Suggestions

- Use larger plants or built screens to block wind for new or tender plants.

- Choose porous fences that allow wind to move through the site more naturally.

- Apply thicker mulch and more frequent supplemental water to new plants at the base of solid fences.

Small Shared Space

There are a few special considerations when you are working in the small urban landscape that is shared by multiple users or infrastructure.- Privacy needs – space is shared with tenants or viewed by neighbors

- Snow storage in winter and into spring (and due to the small space, sometimes it’s your neighbor’s snow too)

- Street side parking areas

- Contested boundaries with neighbors

- Overhead wires and poles, and underground wires and pipes

- City infrastructure (transformers and streetlight boxes) might need to be screened from view or simply incorporated into the design as is. Snow storage in winter and into spring (and due to the small space, sometimes it’s your neighbors’ snow too)

Suggestions

- Call DigSafe before digging, even for planting trees and shrubs.

- Use plants that die back to the ground in areas where snow is stored to prevent plant damage.

- Consider including neighbors in part of the design process to decrease potential conflicts during installation.

- Find out if there are regulations for plant distance or height limitations for city or utility infrastructure.

Other Factors

An urban site might present one or more other unusual or unexpected circumstances.- Animals – dogs, skunks, opossum, rats, deer, turkeys, squirrels

- Zoning – sometimes current zoning practices limit what you can do. Many zoning plant height limitations for front yards are interpreted specifically for grass height. Perennials, shrubs, and trees may not apply to vegetative height limitations, but clarify with the town or city as needed.

- Regulations by special interest groups like condo or historic associations

Suggestions

- Place stones, garden sculpture, wattling, fences, or larger plants around small, new plants to deter animals from digging until new plants become well-rooted.

- If rats are a problem, cover all water sources, only compost in sealed bins, and add wire fencing around outbuildings that extends 12” below grade to prevent burrowing.

- Great designs and great plants win over many of the most cynical community members.

- Show successful precedents to community groups and condo committees to gain interest and approval in the project.

Design Challenges

Urban conditions present more difficult challenges for landscape design and plant selection than most other sites.Excess Material

Soil amendments can create excess material for a small space. Uses for excess soil include making berms, spreading out over rest of yard, giving away, or removing from the site.- Exposed soil loses moisture more rapidly than covered soil.

- If the soil is contaminated, there is added cost for removal as a toxic substance.

- Even if contaminated, it’s usually best to try to keep the soil on sight.

- Small sites might have limited or no access to get materials on and off site.

Suggestions

- Consider not amending the soil and move on to the section immediately following this one.

- If access is limited, build up organic matter a little at a time.

- Create berms, raised beds, or planters to use the increased material created by amending soil.

- If significant soil contamination is suspected or known, edible gardening can be done in raised beds or containers. Keep soil covered with groundcovers or mulches to prevent splash-back and dust accumulation. Wear gloves and wash hands and clothing after gardening; remove shoes before entering house.

- Rotating compost bins are usually small enough for small sites. They break down organic matter faster than piles, so you can use yard waste faster.

Right plant, right place

We hear this advice frequently, but can we adopt it as a practice for finding plants that will thrive with your urban site conditions, as is, instead of trying to amend the soil? There are plants that grow on beaches, in mountain scree, deserts, cracks of city sidewalks, and abandoned parking lots. We should be able to find desirable native plants that will successfully grow in city conditions. Use your challenging site conditions to create unique designs and interesting plant communities.- Native plants grow in a variety of spaces and are often more flexible in their tolerances of various conditions than the preferences stated in publications. For example, Dicentra eximia (wild bleeding heart), grows well in both moist, shady woodlands and dry, sunny gravel.

- An intentional blending of native species with non-invasive, unaggressive cultivars and non-natives that offer desirable characteristics, can provide an ecologically balanced, but flexible strategy for urban design.

- Plant diversity has been lacking in the city, but we can intentionally bring biodiversity into our urban designs and increase support of a variety of ecological functions.

- There could be high root competition from other vegetation, possibly including invasive plant species.

Suggestions

- Cultivars might offer desirable characteristics for small sites: smaller size, less suckering, or less aggressive reseeding.

- An adequate layer of high quality mulch, like leaf mold, can decrease tree transpiration by up to 25%.

- Compile a list of plants that grow where you’d least expect or in a variety of natural ecosystems.

Small Garden Spaces

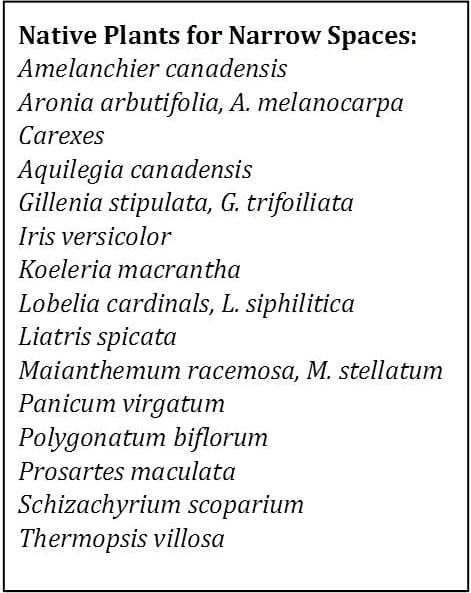

Potential garden space is limited between vehicles, sidewalks, roads, driveways, houses, and other buildings. These spaces might be very small or very narrow and accumulate salt and pollutants that become concentrated in the small area. There are limited plant choices for the limited the space and challenging conditions.

Potential garden space is limited between vehicles, sidewalks, roads, driveways, houses, and other buildings. These spaces might be very small or very narrow and accumulate salt and pollutants that become concentrated in the small area. There are limited plant choices for the limited the space and challenging conditions.

Suggestions

- Choose plants that, when full-grown in 3-5 years, will not crowd the site or adjacent areas like driveways and sidewalks.

- Small trees and shrubs can fit under wires, small or narrow plants can fit in narrow areas.

- Using techniques such as espalier and trellising take advantage of vertical space.

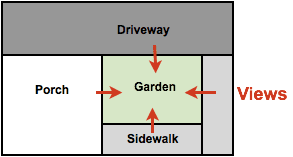

Viewing Gardens from More than One Direction

Small gardens are viewed up close from multiple directions.

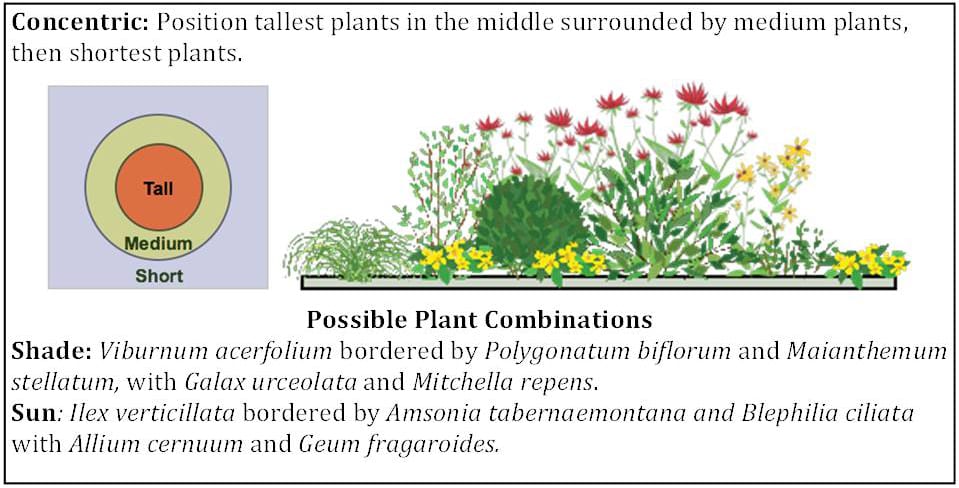

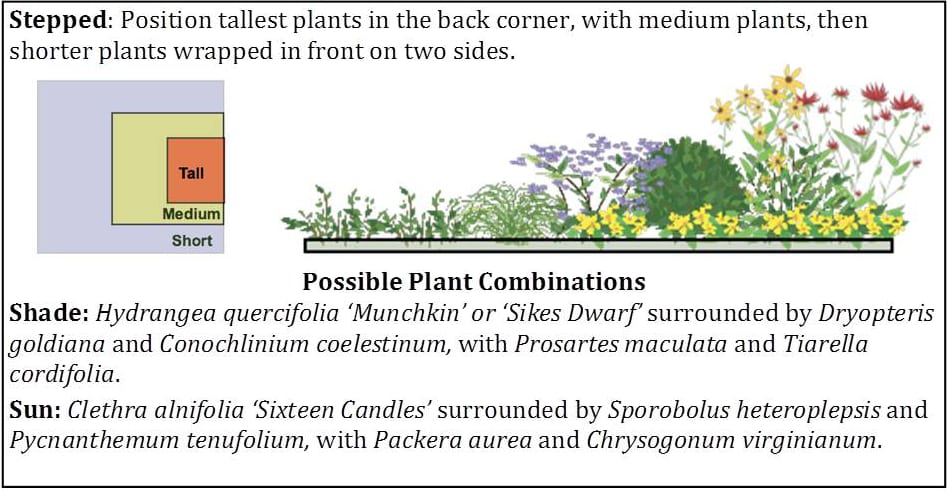

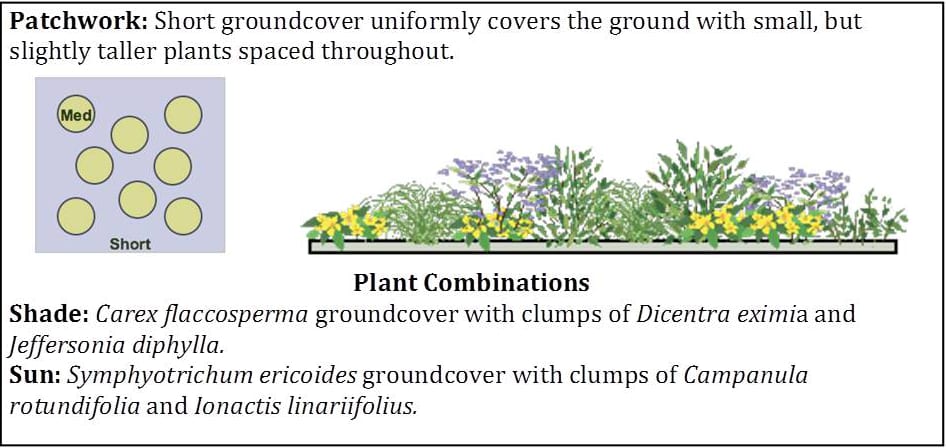

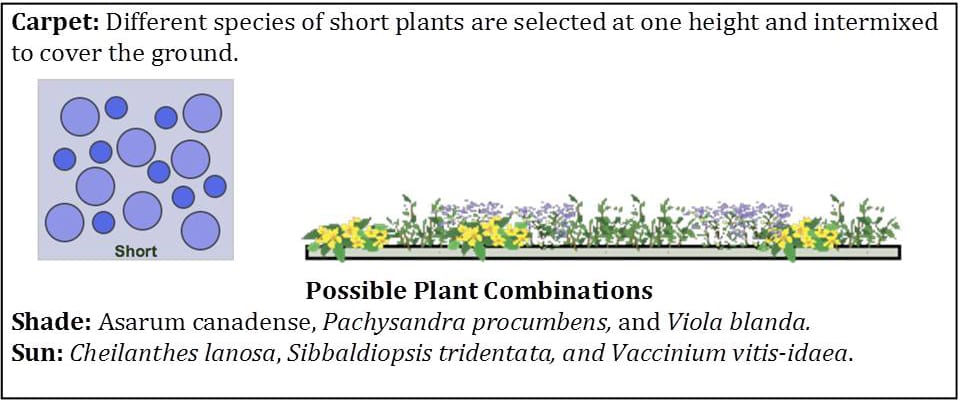

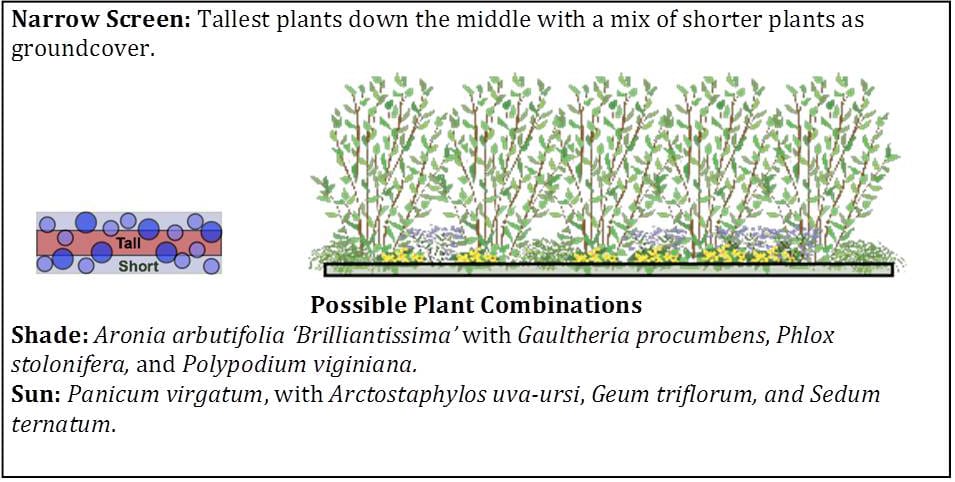

Examples of Design Styles for Gardens with Multiple Viewpoints

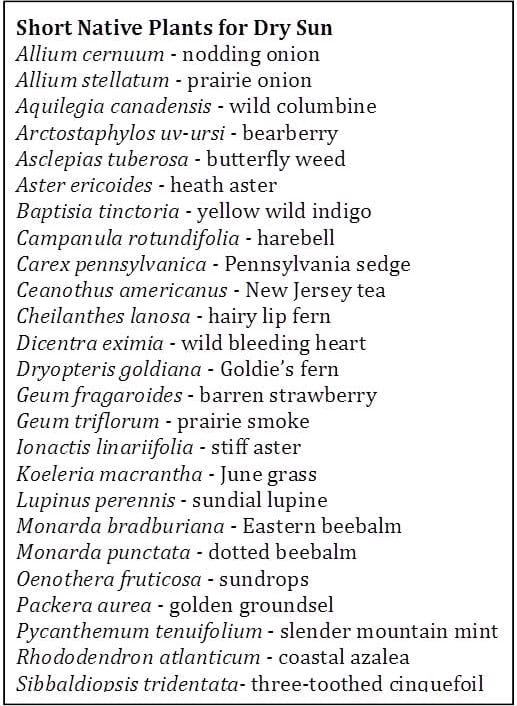

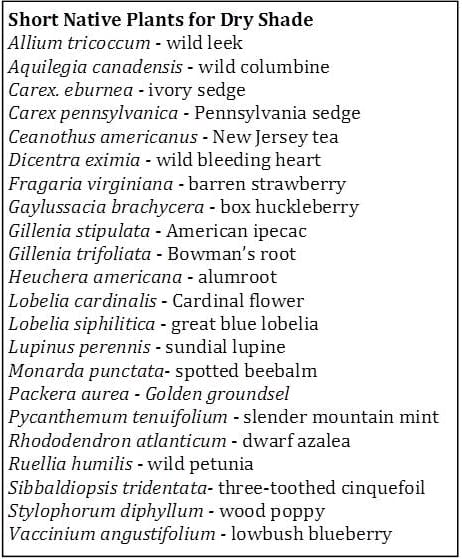

Following are some design strategies with suggested native and native cultivar plant combinations. The strategies using taller plants could easily be adapted and maintained for areas as small as 5’ x 5’. Those strategies using only small and medium plants can be adapted to any small garden.