Gypsy Moth Control

It’s that time of year when we see gypsy moth caterpillars emerge and wreak havoc on our trees. You won’t ever completely eliminate this insect, but you can control some of the damage. Spraying insecticides kills pollinators, other beneficial insects, and often birds and toads. So besides having a professional come spray your affected trees, there are some strategies you can use to help decrease the caterpillar invasion. Check the website GypsyMothAlert.com for a great pictorial of gypsy moth control strategies for the homeowner, as listed below:

1. Use duct tape and tanglefoot on trees.

2. Wrap trees with folded burlap strips.

3. Wrap trees with burlap strips sprayed with insecticide (can kill beneficial insects too).

4. Use gypsy moth traps.

5. Learn to identify gypsy moth egg masses and destroy them: Massachusetts Gypsy Moth Fact Sheet

6. Aid the spread of virus fatal to gypsy moths.

7. Encourage birds to visit your property. Plant a variety of plant species that provide refuge, nesting, and food throughout each season. ensure there is a clean water source nearby.

Attract Butterflies and Moths to Your Garden

The idea of supporting more wildlife in your yard can be expressed in many ways. It might be that you want to provide food for birds, attract butterflies, create safe small mammal pathways, or improve pollinator resources. Animals and insects need a variety of plants, both bare and planted areas, plant litter, and deadwood for safety, food, and different stages of growth. When it comes to ecological health and diversity, a spotless yard is not a healthy yard.

Some of the strategies you can use to meet these goals are rather broad and simple:

- Stop using pesticides: insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides, etc.

- Choose a variety of flowering plants and stagger bloom times throughout the year.

- Chose plants of different heights to create layers in the garden.

- Designate areas in your yard that you don’t mow.

- Make your lawn smaller or eliminate it completely.

- Don’t remove all your fallen leaves and yard waste – mulch with them or allow a few piles to remain in out of the way spots, such as under shrubs or corners of the garden. Butterflies and moths often overwinter in curled up fallen leaves. Insects often pupate or overwinter in hollow plant stalks.

- Leave some patches of earth bare of leaves and mulch for ground-nesting bees.

- Ensure that there is clean water nearby (without pesticide and fertilizer runoff).

If you are interested in choosing plants that will support more wildlife in your yard, please look over this list of Plants to Attract Butterflies and Moths by Doug Tallamy, entomologist, professor, and author. When you make habitat for butterflies and moths, you are also creating habitat for other beneficial insects and wildlife.

Clean Water Is Healthy Water

Stormwater management is an important element that separates sustainable and ecological landscape design from conventional, unmanaged landscaping. Stormwater runoff is often contaminated with various substances like fertilizers, pesticides, road salt, oil from cars, trash, sediment, grass clippings, pet waste, and farm waste. These pollutants make their way from yards, driveways, and parking lots into water as rain falls and runs through the landscape, but then it keeps going and eventually makes its way into rivers, lakes, ponds, vernal pools, and oceans.

This pollution affects our quality of life. Many rivers and lakes aren’t clean enough to swim in and fish caught from them can’t be safely eaten. Even many of the the ponds and lakes that offer swimming need to be closed frequently due to dangerous algae blooms that result from the water having too many nutrients, an process called eutrophification. Fertilizers from lawns and gardens get washed into the water and create the perfect growing conditions for bacteria and algae overgrowth. Pollutants also find ways into wells and public water supplies, increasing the cost of maintaining safe drinking water. Research published in the American Journal of Public Health found that “the estimated annual cost of waterborne illness is comparable to the long-term capital investment needed for improved drinking water treatment and stormwater management.” Properly managing stormwater pollution can directly impact public health and decrease costs associated with treating waterborne illnesses.

Below is one of the first simple, usable criteria I have seen for determining a site’s level of risk for adequate stormwater management (from Penn State; adapted from the Univ. of Nebraska). Tools like this should be adopted to improve awareness about the quality and quantity of stormwater runoff in our communities. By identifying high risk conditions and implementing some simple strategies (think downspout redirection into gardens, choosing deep-rooted plants, decreasing lawn area, and building raingardens), we can decrease the amount of contaminated water running off a site. Whatever water does leave the site could be much cleaner, and clean water is healthy water for us all.

Water Management/Runoff Scorecard:

Death to the Butterfly – Cutting Back and Raking Up

Summer has rapidly receded, and the autumn colors and cool nights herald the end of the growing season. You might be tempted to go clean up your gardens, but the fallen leaves and dead stalks of plants have great value to many birds, small mammals, and insects, including butterflies. And who doesn’t like butterflies? (Well, I do know one person.) Many people like the idea of attracting butterflies to their gardens and advocate protecting them, but fall cleanup can jeopardize these same butterflies. “How can that be?” you might ask. Below is a list that someone compiled and posted here about the strategies that butterflies use for overwintering:

- Fourth-stage caterpillars hibernate in rolled leaves on the ground.

- Third-stage caterpillars make a shelter from a rolled leaf tip in which to spend the winter.

- Partially-grown caterpillars hibernate at the base of the host plant.

- Overwinters as a caterpillar in seed pods of food plant.

- Overwinters as a caterpillar in silken nests below host plants on ground.

- Overwinters as an adult in the shelter of hollow trees, under bark or utilize seasonal outbuildings.

- Hibernate as adults. For protection they use hollow logs, woodpiles and loose bark.

- Overwinters as a young caterpillar in a hibernaculum (rolled leaf) on host plants.

- Caterpillars overwinter in leafy case on host plants.

- Overwinters as caterpillar in leaf tip shelter.

I found this information very interesting. We know that monarchs migrate, but other types of butterflies use a variety of methods that are dependent on leaf litter and dead plant material to survive through the winter into the next spring season. You can imagine how cleaning up all your leaves and carting them away can have a negative impact on the next year’s butterfly population, and the next year’s, and the next.

This article by the PennState Extension provides some simple guidelines for fall cleanup, and identifies which areas are reasonable to clean up (like your vegetable garden) and which to allow to naturalize through the winter. If you’re seeking to adopt more ecologically-friendly habits, please consider leaving most of your leaves and dead plants in place through the winter. Save the cleanup for spring instead – after the redbuds and dogwoods start to bloom. You’ll find that you have some additional free time during the fall too!

Dancing in the Moonlight

Dicentra cucullaria (Dutchman”s breeches)

Nighttime in the garden is a magical place, with silverly moonlight caressing leaves and flowers as they sway in a light breeze, the flowers’ fragrance meanders then lingers with the music of nocturnal creatures. The transformation made by moonlight on plants and water and the coolness of the night made moon gardens a popular feature in hot climates. Gardeners chose plants that glowed in the moonlight or infused the air with enticing scents, adding water features that mirrored the moon and stirred silver streams and droplets here and there. Moon gardens became popular in the 1920’s and 1930’s in England and the U.S., but they were somewhat forgotten as people spent more time indoors and the great American lawn replaced flower gardens.

I’ve always had a fascination with moon gardens, though, and I recently began to wonder what native plants would be suitable for nighttime interest. Below is a partial list of North American native plants, predominantly of the Northeast, that could enchant both the moon and you with their blooms and scents. These plants also provide a host of ecological benefits to native pollinators, other insects, and wildlife. As always, choosing the right plants for your site can help decrease water use, maintenance, erosion, and the heat island effect, while providing increased beauty.

Spring: Actaea recemosa and A. pachypoda, Dicentra cucullaria and D. eximia ‘Alba’, Houstonia caerulea, Phlox divaricata and P. stolonifera, Tiarella cordifolia, Trillium grandiflorum and T. luteum, Magnolia virginiana and M. macrophylla, Halesia monticola, H. tetraptera, and H. carolina, Cephalanthus occidentalis, Chionanthus virginicus, Cornus florida, Aronia arbutifolia and A. melanocarpa, Kalmia latifolia, Rhododendron groenlandicum.

Summer: Allium cernuum and A. tricoccum, Anemone virginiana, Aruncus dioicus, Baptista alba, Echinacea purpurea alba, Geranium maculata, Gillenia trifoliata, Hydrangea quercifolia, Koeleria macrantha, Liatris spicata alba, Maianthemum racemosum and M. stellatum, Phlox paniculata, Physostegia virginiana, Polygonatum biflorum, Rosa blanda, Lobelia cardinalis “Alba”, Ceanothus americanus, Clethra alnifolia, Itea virginiana, Rhododendron arborescent, Viburnum lantanoides, V. lentago, and V. nudum, and Viola walteri ‘Silver Gem’.

Late summer/autumn: Achillea millefolium, Actaea rubifolium, Ageratina altissima, Agrostis scabra, Amsonia tabernaemontana, Andropogon virginicus, Ascelpias verticillata, Clematis virginiana, Doellingeria umbellale, Eurybia divaricata, Heuchera villosa, Hibiscus moscheutos, Monarda punctata, Muhlenbergia capillaris, Nymphaea odorata, Panicum virgatum, Pycnanthemum tenuifolium and P. virginianum, Sanguisorba canadensis, Symphyotrichum erecoides.

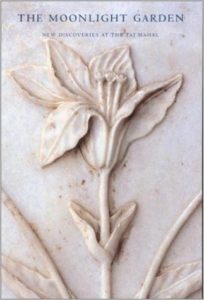

If you are interested in reading more about moon gardens and the discovery of the gardens that existed at the Taj

If you are interested in reading more about moon gardens and the discovery of the gardens that existed at the Taj

Mahal in the 1600’s, read The Moonlight Garden: New Discoveries at the Taj Mahal, by Elizabeth B. Moynihan. A short history of moon gardens can be found in this post from Don Statham Design in New York.